Chances are that even those unfamiliar with Star Wars will immediately recognize a Death Star. That’s because, since the beginning, the franchise has shown as many on-screen super weapons as temperate planets. The sizzle reel for The Rise of Skywalker makes it seem like we’re probably going to get another one, particularly when factoring in J.J. Abrams' love for symmetry in the original trilogy and the arms-race trajectory of the sequel films.

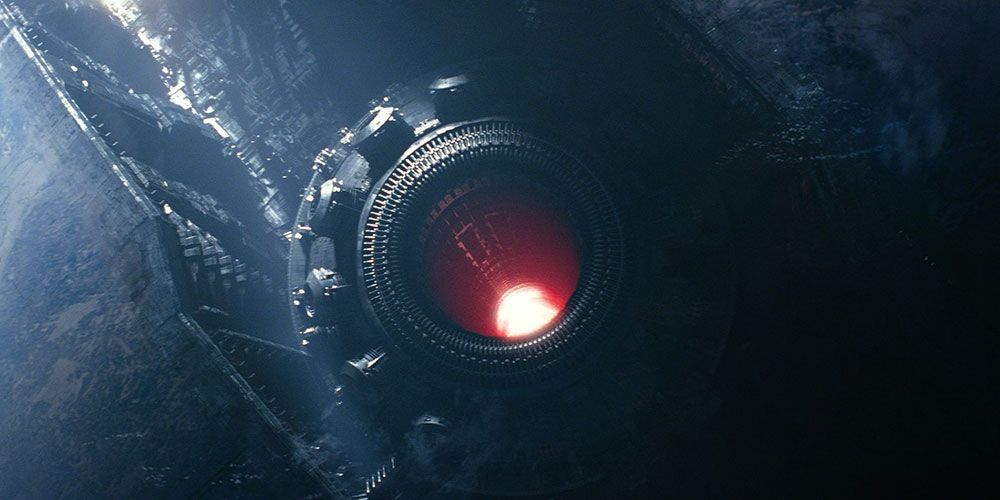

Some readers might argue that the franchise is called Star Wars, so super weapons are expected, and that Abrams isn’t planning for yet another planet-destroying Death Star or system-destroying Starkiller Base, but rather for a massive fleet of Star Destroyers equipped with red-beamed cannons… but that is like failing to see the forest for the trees.

In a way, it almost makes it worse: The proliferation of these miniaturized super Star Destroyers could turn any rogue captain into a planet-killing, genocidal monster even after the First Order is dismantled. This would mean that galactic peace could never be achieved; not really. Not even after the much hyped fairy tale “satisfying” ending promoted by the cast and crew.

Cinema doesn’t exist in a vacuum. George Lucas modeled the Empire after Nazi aesthetics. The First Order is the refined and amplified version of the Empire; just look at General Hux’s "Triumph of the Will" speech before he obliterates an entire planetary system. Nazi aesthetics are an easy visual shortcut to telegraph to the viewer who the bad guys are, just like the Death Stars and their derivative products are the galactic equivalent of Earth's nuclear weapons.

The original trilogy worked as a clear-cut epic fairy tale. The Death Star-Nazi aesthetic visual combo told us that only someone as powerful and evil as the Empire would be able to develop weapons of mass destruction. Only the Bad Guys would be capable and willing to destroy the galaxy instead of ruling it, and that, as far as the good rebels slew the dragon, the destruction would come to an end, the day would be saved and everyone would live happily ever after.

This was subverted from the beginning in The Force Awakens. Now it wasn’t a massive Empire drawing on semi-legitimate state power to build a super weapon, it was the rogue wannabe First Order succeeding to do so. The new Starkiller Base wasn’t just capable of destroying entire systems, but also of drinking suns. Its red beams could strike across the galaxy, like nuclear long-range missiles. Suddenly, the threat of total destruction was omnipresent and insidious, mirroring real-world fears of terrorist organizations and warmongering nations being able to kill anyone, anytime, anywhere.

Suddenly, Star Wars hit too close to home.

One of the biggest criticisms of Abrams’ Star Trek reboot, particularly Into Darkness, was that he took the pacifistic premise of exploration and turned it into a heavy-handed deep state war conspiracy. However, this was also its redeeming quality. A harsh light was shown on the paranoid, preventive strike-obsessed and power drunk military mindset of Starfleet, which looked and sounded suspiciously like the military branch of the United States; an almost self-reflective exercise.

In contrast, the Star Wars sequel trilogy doubles down on the concept of righteous paranoia and constant vigilance. A powerful Dark Lord could be worming its way inside a child’s head, slowly radicalizing them to a kamikaze cause. In the sequels, the Phantom Menace is more real than it ever was in the prequels. The Resistance could lose everything at any given moment, and they are still visually coded as American cowboys and elegant first ladies.

So, is this military narrative framework a healthy one? If the audience of a fairy tale knows that the dragon will come back every three years for a new installment, isn’t the act of slaying it moot? If now a single ship can destroy a planet, how could the good guys ever truly win the day and rest? Who benefits from this cycle of violence, and is it even necessary for Disney to continue down this path going forward?

Disney will benefit immensely from this ongoing fictional conflict; those LEGO Death Stars and Darth Vader Barbies aren’t going to sell themselves. Just like the wealthy weapon dealers of Canto Bight, a large part of Disney’s profit depends on accelerating their toy arms race, reaching either into the past conflicts of the franchise or laying the groundwork for future galactic wars.

The upcoming Disney+ series The Mandalorian and the Cassian Andor series will be heavily armed to deal with the past. We can only hope that any narrative set after The Rise of Skywalker moves away from the tired and too real threat of weapons of mass destruction, and closer to the joy of exploring an entire living galaxy far, far away.

Directed and co-written by J.J. Abrams, Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalkerstars Daisy Ridley, Adam Driver, John Boyega, Oscar Isaac, Lupita Nyong’o, Domhnall Gleeson, Kelly Marie Tran, Joonas Suotamo, Billie Lourd, Keri Russell, Matt Smith, Anthony Daniels, Mark Hamill, Billy Dee Williams and Carrie Fisher, with Naomi Ackie and Richard E. Grant. The film arrives on Dec. 20.

Add Comments